Historically, I have a very good track record of predicting mortgage rates – nowadays though it’s feeling more 50/50. If you ask “what will rates be like in the next 12 months?”, you’re likely to get a more unsure answer than if you were to ask “where will rates be in 3 years?”

Why? Because we have a confluence of competing economic factors and it’s almost impossible to tell with certainty which will win.

One the one hand, Canada’s economy is facing some pretty substantial challenges.

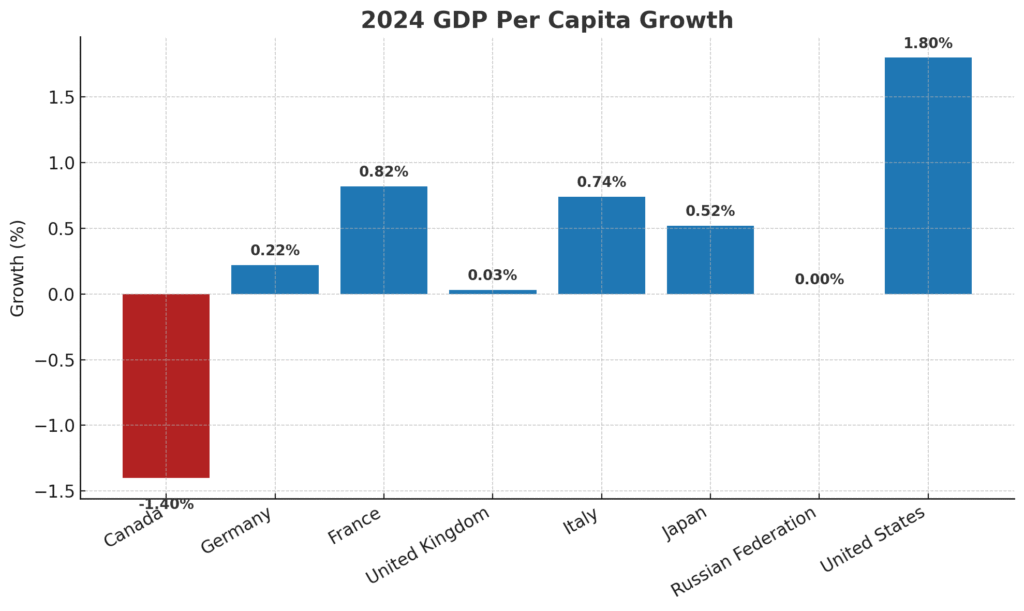

We’re almost the bottom quartile for unemployment rates amongst our G20 peers (beating only France, Argentina, Turkey, Spain and South Africa). We’re seeing an unprecedented flow of capital out of Canada’s economy ($8.3 billion in June alone) as foreign investors run from Canada’s pitiful financial mismanagement. And, if you look at us from the GDP growth per capita, we’re the worst performing country in the G8.

All of these things, are recessionary in nature – which if we go back to our entry level economics class, tells us that rate cuts should be coming… (Bring rates down, so people spend more money, which stimulates the economy.)

The problem however, as I’ve pointed out before in my writings, is that Canada doesn’t live in a vacuum.

We have both domestic and international forces that also have an upward pressure on rates.

Canada’s government has spent more in the last 10 years the every other government in the history of this country…combined. This is inflationary in nature. And despite all of the inflation effects we’ve already felt, the odds that all that inflationary pressures have been accounted for is 0%. It could be a decade, maybe even longer, until the full effects have been felt.

Which means higher rates. (Increase rates, so it costs more to borrow, so less people spend money in the market, so prices slow their ascent.)

Throw in some tariff complications (recessionary short term, inflationary long term), potential amendments of CUSMA in 2026, foreign investors selling off a net 2 trillion yen in Japanese government bonds (which increases the yield of the second largest bond market in the world and in turn, has an upward pressure on all worldwide government bonds, which in turn should pressure fixed rates up), and a whole lot more.

Cutting through all the noise, it’s important to note that at present, the recessionary pressures in Canada seem to be more pressing and we’re seeing the effects of that with BoC policy (and consequently the return of lower fixed rates that we saw earlier in the year).

By this time next year however, my money is on rates higher than we’re seeing now. The long-term forces (logically) point to up. But once again, who knows. Maybe Trump will get his way and pressure the Feds into a reduced overnight lending rate – in which case, we’ll see lower.

When has renegotiating your mortgage ever felt more like gambling?